The Glory Years

by Tom Ellis III

| Paul Butterfield The Glory Years by Tom Ellis III |

"I don't lead musicians, man. They lead me. I listen

to them to learn what they can do best. That's what gives

playing that feeling, like when you see a pretty woman and say,

'Shit, wait a minute.' Listening to what they do and

feeding it back to them is how any good bandleader should lead

his musicians."

-- Miles Davis on musical guidance

"I've got to keep people like that around because

on any given night I might play better than them, or they might

play better than me. It's that challenge that makes

the music happen. You've got to read people, what's

happening in their lives; that's what enables you to inspire

them with your music."

-- Saxophonist David Murray on his music's intersection

of the planned and spontaneous

By the end of 1965 the Butterfield Blues Band had undergone the first of a series of personnel changes that would continue on throughout the next six years, each marking a subtle shift in the band's sound and direction.

When Mike Bloomfield joined in early 1965, he probably did so

with some trepidation. Butterfield was aware of Bloomfield's

playing from his long-standing gig at the Chicago club Big John's,

but it wasn't until the band was about to go into the studio

to record its first effort with producer Paul Rothchild (recently

released as The Lost Elektra Sessions) that Butterfield

felt the need for a lead guitarist. Even as accomplished as he

was on guitar, Bloomfield viewed Butterfield as a musician at

another level.

"When I was around 18 years old, I had been sort of messing around, and Paul sort of accepted me," Bloomfield remembered in 1968 for Rolling Stone. "Well, he didn't really accept me at all, he just sort of thought of me as a folkie Jew boy, because Paul was there, and I was just sort of a white kid hanging around and not really playing the shit right, but Paul was there, man."

And although their personalities might have been very different, their dedication to the music forged a common bond. "I didn't dig Butter, you know. I didn't like him," Bloomfield said. "He was just too hard a cat for me. But I went to make the record, and the record was groovy, and we made a bunch more records. One thing led to another, and he said, 'Do you want to join the band?' And it was the best band I'd ever been in. Sammy Lay was the best drummer I ever played with. Whatever I didn't like about Paul as a person, his musicianship was more than enough to make up for it. He was just so heavy, he was so much. Everything I dug in and about the blues, Paul was."

Bloomfield's brother, Allen, thinks "Paul fascinated and intimidated Michael. Paul was to Michael a pretty threatening guy, because if you screwed with him he would fight back. Mike would use his mouth to try to avoid a problem, but Paul would never buckle under. So Mike acquiesced to that 'potency' that Paul had. But he immediately recognized the virtuosity of his playing -- he was in a league with the best of the Chicago guys. There was just an attitudinal problem between the two -- Paul was the hard ball bearing and Mike the soft marshmallow. It took a certain period of time before Paul recognized that underneath that veneer there was a sincerity and an earnestness. Mike had to be the very best he could be on his ax. And when he finally heard that, he let Michael do whatever he wanted. That was the common denominator. He saw Mike as a player."

By the summer of that year, any skepticism Butterfield had about Bloomfield had dissolved, and the musical communication between the two was obvious. "I remember sitting with Paul at a bar, probably the Bitter End, across Bleeker Street from the Cafe au Go-Go," notes Mark Naftalin, "and he told me that there was no guitarist in the country he'd rather have with him than Mike Bloomfield. I thought the band was screaming then. The effect of Paul and Mike mixing and matching was dizzying, and Mike and Elvin Bishop's guitars, when they were working together, made a beautiful section."

Naftalin himself became the sixth band member. Although Butterfield and Bishop were familiar with him during his days as a student at the University of Chicago, it was while he was studying theory and composition at the Mannes College of Music in New York City that he was asked to join (initiating a long relationship between Mannes and the Butterfield bands).

"The band was in the studio working on the first Elektra album," he remembers, "and I came by one of the sessions, hoping to sit in. Paul and Elvin knew me a little and had heard me play -- I used to pound it out on an unamplified acoustic piano when they played at U. of C. twist parties, and that summer I had sat in, or played along, with the band, once again on unamplified acoustic piano, for a couple of sets at the Cafe au Go-Go in the Village. On this particular day Elvin wasn't around as the session began, so they put the organ on his track and tried one with me playing. This was 'Thank You Mr. Poobah.' The band seemed to like the sound with the organ, and Paul asked me to keep playing. Elvin arrived, and we shared his track. During the course of the session Paul invited me to join the band and to go on the road with them to Philadelphia that weekend. I accepted." Eight of the 11 songs on the first album, including "Thank You Mr. Poobah," were recorded at that session.

The band, now six pieces, was soon back in Chicago for gigs at Big John's for six weeks, then returned to the Unicorn Pub in Boston. It was there that the Butterfield Blues Band began working on a new experimental song that would alter the band's performances and radically expand its reputation for years to come.

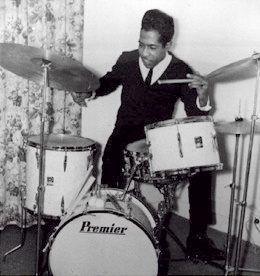

Billy Davenport started playing drums in 1939 at the age of six, when he found a set of drumsticks in his South Side Chicago neighborhood. A child prodigy, he was blessed with parents that were extremely supportive of his talents, and during the next 20 years he pursued life as a jazz drummer in groups in high school and the armed forces, intermixed with straight gigs with small swing combos that played Chicago's active jazz scene.

"I grew up on Benny Goodman and Gene Krupa," Davenport says. "In my neighborhood there were all kinds of clubs, so I got to hear Billy Eckstine's big band, Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker -- all those people. At the Persian Ballroom -- I think it was 50 cents to get in -- everyone played there." Davenport was also very into Art Blakey and Max Roach. "I saw Gene Ammons and once got into a jam session with Sonny Stitt."

But by the mid-1950s a change was underway in Chicago -- jazz was waning. "I realized around then that you couldn't make it in jazz unless you got with a big band. So I fell to the blues. Like a guy told me one time, 'Take what you know and add to it, and it'll come out alright.' "

By 1961 he was married and playing with Otis Rush. "I played

with Otis for about a year, and then I went with a harmonica player

named Little Mack Simmons, and through him I made contact with

Little Walter. I used to sit in and play with him at his gig after

I finished up with Little Mack Simmons. But Walter never liked

me too much. He said I did too many rolls -- the kind of blues

he played wasn't it." Other gigs with Junior

Wells, Syl Johnson and again with Rush followed. "Then around

the end of 1964 I met this young man named Paul Butterfield. I

was working at Pepper's Lounge and he'd come down and

we'd talk, but he never sat in until one Tuesday night --

jam night."

"But it wasn't Butterfield that got me in the band -- it was Mike Bloomfield. He came down one night, and we talked for about an hour. He said some things were going on with the band, and he wanted to know if I was available. I said yes, but I didn't know I wouldn't like the road so much. In early 1965 they were working at Big John's, and I sat in with the band once, but Sam Lay was still with the band. Later that year, after they came back from the Newport Festival, Paul and Elvin came down -- I was working with Jr. Wells -- and talked to me about playing with them. They said they were playing more of a rock groove or swing groove. I said, 'Call me.'"

The call came sooner than expected. Sam Lay became ill in late 1965 in Boston, and was hospitalized in Chicago. "They called me on a Friday night where I was working at Pepper's. They said they were going on the road, and there was a chance to make some real money; at that time I was making around $45 per weekend, and the pay wasn't working out. Paul called me about five times that night, and we talked and I asked him one question -- could I bring my wife. Paul said, 'You can bring your wife or your whole family, but we need you.' So on Monday morning we drove up to Detroit. We rehearsed three numbers that their drummer couldn't do, and Paul said, 'That's it. He's the drummer.' We left almost immediately for Hollywood, California."

During the Boston gig the band had started playing a long improvisation, loosely titled "The Raga," which was soon named "East-West." "We were listening to a widening range of music," recalls Naftalin, "including Indian classical music, particularly that of Ravi Shankar," which obviously impressed Bloomfield. Soon he announced he had had a revelation with respect to Indian music and that he understood how it worked. The band began performing "The Raga."

"This song was based, like Indian music, on a drone," explains Naftalin. "In Western musical terms it 'stayed on the one.' The song was tethered to a four-beat bass pattern and structured as a series of sections, each with a different mood, mode and color. Every section ended with a big build-up of eighth note accents and a climactic break. Some, but not all, of the sections began peacefully and floated along for awhile before building to the break. In each section the soloist chose the mode, and throughout the song the drummer contributed not only the rhythmic feel but much in the way of tonal shadings, using mallets as well as sticks on the various drums and the different regions of the cymbals.

"The first section was Elvin's solo; he set the mood

for the piece. Starting with the second section Michael played

lead on a series of sections where he explored different modes,

or scales, some of which were suggestive of Indian or Arabic music

and some of which were North American, as in blues, country &

western or Mexican.

"The first section was Elvin's solo; he set the mood

for the piece. Starting with the second section Michael played

lead on a series of sections where he explored different modes,

or scales, some of which were suggestive of Indian or Arabic music

and some of which were North American, as in blues, country &

western or Mexican.

"In places Elvin played tamboura-like drones, especially where Mike was experimenting with quasi-Eastern sounds. Elsewhere Elvin played rhythm parts and counter-melodies behind Mike. In some sections the two of them played parts that I would call double-leads. In the last section Paul came in with his solo, driving the tune into the final climax, which included harmonica and guitars at full wail and 'Joy to the World' on the organ in multiple octaves, capped on occasion by a series of musical 'amens.' This was a group improvisation. In its fullest flower it lasted over an hour."

Certainly the "flowering" of East-West, and of the Butterfield

band's expanding musical repertoire, accelerated exponentially

with the addition of Davenport, a percussionist who could

handle many styles and color and decorate long, improvised passages,

something unheard of among blues drummers. Those close to the

band, like Allen Bloomfield, heard the immediate impact Davenport

had on the overall sound and musical direction.

"Sammy Lay came from an R&B background, and as great as he was, he was more straight ahead. 'Mojo' and those songs were quite different from 'East-West'; Davenport was more refined, more delicate. He was very competent. It's possible that 'East-West' wouldn't have happened without him, because he is the source of movement in the song. Billy was so articulate. He was a good jazz drummer and had heard a lot of those guys, especially Max Roach. He was just so refined."

In the early 1950s, when Muddy Waters and other first-generation electric bluesmen plugged in and amplified their rural blues, there was no such thing as a "blues drummer." Muddy pulled Fred Below from Chicago's jazz circles and Below's style set the format for blues drummers from that point forward. Late in the '50s Muddy brought in Francis Clay, another jazz drummer who reinvigorated blues rhythms. Now, nearly a decade later, Butterfield had injected the skills of Davenport, stewing even more jazz percussion back into the mix, opening up the music to improvisation as never before. If Below was the first great jazz drummer in blues and Clay the second, Davenport was certainly the third, and his playing expanded the role of drummer to even greater heights.

"Paul never told me what to play," Davenport says. "He just said to play what I felt was best and try what I wanted. I'd never heard the band when I joined, just been in a jam with them. But when we got to California we spent a week rehearsing, and spent a lot of time on this thing called 'East-West.' It took a while for me to find out what I was going to do -- it was a strange rhythm thing. I first tried to play with a jazz beat, and that didn't work. They kept telling me it wasn't a rock beat or a jazz beat, but in-between -- and I didn't know what the hell in-between was. Then it dawned on me that there was one thing that might work, and that was bossa nova. And that became the pattern for what I played; it started with bossa nova, and I turned it around some and added some things.

"Nobody was playing like that in those days."

As the band grew and its performances began to garner rave reviews, Butterfield was also opening up. When he started the band in the early 1960s, his hard attitude and physical and psychological intimidation seemed molded on the "stone leader" concept of band leaders like Howlin' Wolf and Little Walter. "Paul was very temperamental," Lay told a radio interviewer. "He never did nothing to me, but he would go off on someone else in the band, and I'd have to settle him down." And as a stone leader, Butterfield was taking a bigger share of the money.

But by the time the second Elektra album, East-West, appeared, all that had changed. Conversation and confrontations within the band had led to a more democratic unit, both financially and musically. Everyone was urged to contribute. Butter was no longer always the center of the show. Bishop and Bloomfield were both singing, while Bishop's musical style was allowed to grow and find definition. At some shows Bloomfield stunned the audience by eating fire: In 1995 Al Kooper told Bloomfield Notes that the fire-eating was "as exciting as Hendrix setting his guitar on fire or Townshend smashing his guitar." "East-West," significantly toned down for the album, became a showpiece for the guitarists, and a full-blown musical exploration for all involved.

Butterfield had evolved from the approach of Wolf to that of Muddy, his mentor and great friend. Wolf was the hardened leader, barking orders to his troops, the headliner with a back-up band. Muddy more often took the paternalistic approach -- the leader who let his troops run with their musical abilities, the one who knew the value of a long-time relationship between his musicians and his music.

Butterfield, by letting go of his ego and establishing equality in the group, unleashing his players, and by pushing his musicians to be better while soliciting their input, was expanding the scope of the blues band in the 1960s, much as Muddy had done with his seminal bands of the early 1950s. His own singing and instrumental prowess had also grown beyond that of any living harp player. For proof, listen to The Lost Elektra Sessions, then to East-West: On the former you hear a leader with sidemen, on the latter a cohesive ensemble with shifting personnel in the traditional frontman/leader's role. Butter's singing is markedly different, stronger. His playing is incredible.

The Butterfield Band had become a great band-- and certainly no longer just a blues band. Butterfield was becoming a complete musician with a very effective style of leadership. Both were about to take on a new role they could never have imagined.

This is an abridged version of the Paul Butterfield article. For the complete article, get the hard-copy version of BLUES ACCESS.

Thanks to those who helped in this story, including Peter Butterfield, John Court, Buzz Feiten, Trevor Lawrence, Steve Madaio, Stephen K. Peeples/Rhino, Bloomfield Notes, Ward Gaines and a special thanks to Doug Baldwin, who has been so instrumental in locating Butterfield band members.

|

|