|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

misdiagnosis blues | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

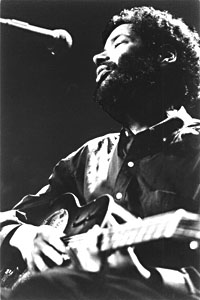

Roko and Adrian Belicís low-budget, highly entertaining film (available very soon, if not already, on home video) tells the story of the unlikely pairing of Pena and the ancient art of khöömei, or throat singing, which the blind San Francisco-based blues musician discovered via a short-wave radio broadcast. As David Feld related in our Fall 2000 issue, Penaís obsession ultimately took him to the poor, tiny south Siberian country of Tuva, where he won the local throat-singing competition and the hearts of the 308,000 local residents. Refreshing, poignant and blissfully free of any pretension, Genghis Blues found a larger audience than expected and even wound up with an Academy Award nomination for best documentary film. At the same time came news that Pena was receiving chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer and doctors had given him only a short time to live. In response to the bad news, long-time friend Jon Waxman made a deal to secure the release on Hybrid Records of New Train, an album recorded by Pena in 1973 which had been squelched by executive producer Albert Grossman and, for one reason or another, had never seen the light of day ó a galling disappointment to Pena for more than a quarter century. Penaís disenchantment is understandable. Though it was written and recorded in Boston with a world-class group that included producer Ben Sidran on keyboards, Harvey Brooks on bass and drummer Gary Malabar, New Train has a loose, swinging, Bay-Area ambience. Out West, Sidran got additional help from Jerry Garcia, who contributes pedal steel to a couple of tracks, keyboard stalwart Merle Saunders, and the incomparably harmonic Persuasions, who contributed background vocals. New Train also includes a hard-rocking version of Penaís song "Jet Airliner." In the liner notes, Sidran explains that Malabar gave Steve Miller a tape of Penaís recording, "and the rest is history." A major song from Millerís re-emergence in 1977, "Jet Airliner" sold many millions of copies, and the royalties have literally kept Paul and his family alive over the years. Now, according to a story in the October 30th San Francisco Chronicle by reporter James Sullivan, Pena reveals that he doesnít have cancer after all. Thatís not to say heís in the clear: Doctors now believe Pena suffers from pancreatitis, not cancer, which means the chemotherapy he had undergone was worthless. Pena, whom Sullivan described as emaciated and very ill, has performed briefly in the Bay Area a couple of times, including a surprise appearance at the San Francisco Blues Festival in September. But his talent seems overshadowed by the circumstances of his life, and our thoughts and best wishes go out to him,. A fund has been created to help Pena with his considerable medical expenses. For more information about the Paul Pena Fund and Pena himself, go to www.paulpena.com; for more on Genghis Blues, check out www.docurama.com; for the country of Tuva: www.fotuva.org. In the same week, Johnny Cash told interviewers that he, too, had been misdiagnosed with a deadly disease, Shy-Drager Syndrome, after he had collapsed while picking up a guitar onstage in 1997. Cash maintains that if he actually had the degenerative, Parkinsonís-like disease, he would already be dead by now.

This is Cashís third album produced by Rick Rubin, whose other work includes albums by rap icons the Beastie Boys and Public Enemy. Probably having been repulsed by the glitzy production values of Cashís slick Columbia recordings of the í80s, Rubin brings the singerís unique vocal gifts front and center where they belong, leaving the instrumentation sparse and in the background. This leaves us to behold Cash as he contemplates his end by putting his imprimatur on songs new and old. Heís able to instill material like "Nobody," written in 1905, with the same kind of power he invests in Nick Caveís contemporary "Mercy Seat," a terrifying roller-coaster ride inside the mind of a condemned murderer as heís being strapped into the electric chair. Every verse ends with the gripping refrain: "And Iím not afraid to die." Most of the attention given Solitary Man centers on Cashís use of material from rock heroes like Cave, U-2 (Cash turns the universal anthem "One" into a very personal folk song) and Tom Petty, whose "Wonít Back Down" is done so well it seems to have been written for the occasion. But Cashís own songs and choice of traditional material ring the truest. "Fields of Diamonds" uses a light folk melody reminiscent of "Ring of Fire" to meditate upon the cosmos, with otherworldly harmonies from the unlikely pairing of June Carter Cash and Sheryl Crow. "That Lucky Old Sun (Just Rolls Around Heaven All Day)," which Cash says won him a singing contest when he was 13 years old, makes death sound like a lazy old sunny afternoon, while "Before My Time" is a moving tribute to his musical ancestors. "Iím Leaviní Now," an older Cash song, takes on new meaning in this context, and the closer, "Wayfaring Stranger," could ably stand as the singerís last will and testament. There are those who might argue that Johnny Cash doesnít fit the strict definition of a bluesman, but to me Solitary Man, like much of his best output over almost 50 years, has the feel of great blues. If you like Solitary Man, you might turn to his recent three-disc set, Love, God and Murder (Columbia Legacy). Compiled by Cash himself, the program shows his preoccupation with three of the bluesí major themes and finds him dealing with them as only the very best can do. And if it isnít the blues album title of the year, Iím a member of the Backstreet Boys. ó Leland Rucker Former BLUES ACCESS managing editor Leland Rucker now edits web sites for a living when heís not working on his golf game.

|

|

|

Like

many people, I had never heard of Paul Pena until last year, when I

chanced upon a screening of Genghis Blues at the local university.

Like

many people, I had never heard of Paul Pena until last year, when I

chanced upon a screening of Genghis Blues at the local university. If

his new album is any indication, Cash has thought a lot about death

since the diagnosis. American Recordings III: Solitary Man (American)

is a compelling portrait of a person facing the end of his life.

If

his new album is any indication, Cash has thought a lot about death

since the diagnosis. American Recordings III: Solitary Man (American)

is a compelling portrait of a person facing the end of his life.