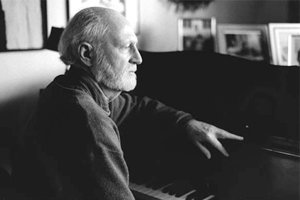

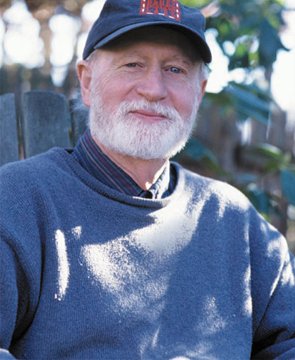

"If you describe on a map a circle with its center at Moorhead, Mississippi, the place where the Southern cross the Yellow Dog, lying within a hundred-mile radius are not only Como and Hernando, but also Red Banks, Helena, Lyon, Leland, Rolling Fork, Corinth, Ruleville, Greenville, Indianola, Bentonia, Macon, Eden Station, West Point, Tupelo, Tippo, Scott, Shelby, Meridian, Lake Cormorant, Houston, Belzoni, Bolton, Tunica, Yazoo City, Lambert, Vance, Burdett, and Clarksdale, whence come Gus Cannon, Roosevelt Sykes, Son House, Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters, Fat Man Morrison, Charlie Patton, B.B. King, Albert King, Skip James, Bo Diddley, Emma Williams, Howlin’ Wolf, Elvis Presley, Mose Allison, Big Bill Broonzy, Willie Brown, Jimmie Rodgers, Robert Johnson, Booker T. Washington White, Otis Spann, Bo Carter, James Cotton, Tommy McClennan, Jasper Love, Sunnyland Slim, Brother John Sellers, and John Lee Hooker. Also within this radius are Greenwood, where Furry Lewis was born, and Grenada, where John Hurt died." — Rythm Oil: A Journey Through the Music of the American South by Stanley Booth Last November 11, Mose Allison, the composer-pianist-singer, turned 70. It seemed a proper time to look in on him and see how life as a senior citizen is for the man once called — 40 years ago in an album title — Young Man Mose. I found out there are problems. One problem is, he’s not acting his age. He’s running and exercising, playing international gigs, has a new album and is still on the lookout for tunes. Another problem, he’s still, in his phrase, "the man without a category." Is he a jazz player? Yes. Is he a blues man? Yes. "To me," Allison said, "it all comes from the same place." Though he left there more than a half century ago, the accent and the — soul? — of the country are still very much part of Allison. Tippo, pop. 200, Allison’s birthplace, is 45 miles from Moorhead on Mississippi Highway 8, between Effie and Needmore in Tallahatchie County, deep in cotton territory. Tutwiler, in the same county, is where W.C. Handy saw a man at the train station playing a guitar with a knifeblade and singing the words, "Goin’ where the Southern cross the Dog." The man was singing about two railroad lines, the Southern and the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley, known also as the Yazoo Delta — and, in the poetic parlance of the common people, the Yellow Dog. Right then and there, Handy said, "Life took me by the shoulder and wakened me with a start." Jazz and blues didn’t exist as musical genres in 1903, when life awakened Handy. According to Allison, they really should never have been separated: "Up until recently, all the great jazz players have played the blues. Louis Armstrong played and sang the blues all the time. So when the country blues players were discovered later, people started to discriminate between that type of blues and the kind of blues jazz players played. You don’t hear too much classic blues playing today when you hear jazz, but all the great jazz players did it." As Allison explained to me, his birthplace was outside Tippo proper: "The place where I was born, my grandfather’s farm, is called the Island because Tippo Bayou encircles it. People had to ford the Bayou to get in and out. They built a bridge when I was growing up, but there hadn’t been one before. It was always called the Island, about an 80-acre farm, completely encircled by Tippo Bayou. "My grandfather had a player piano, and the story is that my father taught himself to play piano by lookin’ at the piano roll, the keys goin’ down and everything. He just evidently had a good ear, and he taught himself to play. He played at parties and things. He played around the house some when I was a kid. I’d hear him — ‘12th Street Rag,’ ‘Sweet Sue,’ stuff like that. He could never figure out why I didn’t try to play that way. When I started playin’ boogie-woogie he didn’t know what I was doin’. "My younger brother did what I was supposed to’ve done: He stayed down there and farmed, went broke," Allison said with a little laugh. "He’s still there, but he’s not farmin’ any more — he had to quit farmin’. That crunch in ’83 when interest rates were 15 percent and commodity prices went down, a lot of them got caught. There’s very few small farmers in the Delta now. He didn’t lose his land. He still rents it out, but he had to get a job. So, that’s what I was supposed to’ve been, but I never did like it." He did his share of it, though — as a boy he plowed mules, picked and chopped cotton, cut and hauled hay. "I’m probably one of the few remaining blues singers with that experience." Allison, who minored in philosophy at LSU, explained to me about personal destiny: "It’s part genes and part means. Are you hip to means? That’s the things you get culturally, y’know. Genes are what you get biologically, means are what you get from the cultural background. There was music in the house all the time. My old man played piano, as I said, and I took to it right away. Lately I’ve been readin’ a lot about the brain, and one of the studies they’ve done with birds shows that a bird can’t sing his song unless it hears it — there’s about three days in there when the bird has to hear its song, or it’ll never be able to sing its song. It’s just a matter of being triggered. The potential is there, and it’s just whether or not you get triggered. I got triggered by my dad bein’ musical and hearin’ music a lot." One of Allison’s cousins was a jazz fan. "She had records of Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Earl Hines, people like that, so I got all of it at an early age. She was my first cousin. She was older than me, but she lived in Mississippi and was goin’ to college when I was a teen-ager, but she had records. I remember even before we had

electricity, the wind-up Victrola. My folks went to dances all the time.

They used to go over to the riverboat and go to dances on it, so I got

access to it at an impressionable age, and it just took, you know. Then

you have to figure in whatever X-principle there, the natural talent, if

you have any and so forth. Which you spend your whole life trying to

prove. Trying to decide whether you have any, or whether you’re just

clever. It’s hard to tell. (laughs)

teen-ager, but she had records. I remember even before we had

electricity, the wind-up Victrola. My folks went to dances all the time.

They used to go over to the riverboat and go to dances on it, so I got

access to it at an impressionable age, and it just took, you know. Then

you have to figure in whatever X-principle there, the natural talent, if

you have any and so forth. Which you spend your whole life trying to

prove. Trying to decide whether you have any, or whether you’re just

clever. It’s hard to tell. (laughs)

"My father had an older brother, but I had a bunch of aunts, and most of them got married, so I had uncles like that, but my grandfather was married three times, and he had three different bunches there. My father was on the second wife, Texana. I always wondered about her, nobody knows anything about her much. She died when my father was a baby. So, who knows? I always figured the musical talent might possibly have come right through her. My father looks like her. But, talkin’ about Tutwiler, there’s a movie theater in Tutwiler called the Tut-Ro-Van-Sum — ’cause of Tutwiler, Rome, Vance and Sumner. I was talkin’ to Muddy Waters about it — he grew up in Tutwiler, y’know. I said, ‘You know about the Tut-Ro-Van-Sum?’ and he said, ‘Man, I used to go to the Tut-Ro-Van-Sum, used to sit in the balcony on Saturdays.’ So it’s a possibility that me and Muddy Waters could have been in the Tut-Ro-Van-Sum Theatre at the same time. ’Course I’d be down in the white section, and he’d be up in the balcony. Watchin’ Hopalong Cassidy or somethin’." One of Allison’s earliest influences was what he calls a "jyuck box." (His Delta inflections give the u in juke a short sound — rhymes with book — while reversing the process with the expression boogie-woogie.) The juke box was at, of all places, a gas station. Your reporter is from the rural South but had never encountered this phenomenon. "There was a juke box at the … filling station?" "Right, that was just sort of a hangout." "And people would come by and drink Co’-Colas and play the juke box?" "That’s right, and beer. That was the beer place. They had beer there, and they had craps, so it was sort of like the local hang. This was in Tippo, at the crossroads. On Saturdays it was like overwhelmed with all the black labor in the area. I remember goin’ over there and listenin’ to the jyuck box at the service station when I’d go over and take a break. It had mostly country blues — I remember people like Roosevelt Sykes and Big Bill Broonzy. "I’ve got a blues line that I consider the quintessential blues line, that nobody can identify. I heard it on the jyuck box in Tippo, Mississippi, and I think it was a woman. I suspect that it was Memphis Minnie. But nobody’s ever been able to identify this thing for sure, and I’ve talked to blues scholars and blues men — B.B. King, John Lee Hooker, Junior Lockwood and all these people. Most of them have heard the line, but none of them remember who did it. Now the line is: ‘Papa’s in the jailhouse, Mama’s drinkin’ wine, sister’s on the corner doin’ the bo’-hog grind.’ The bo’-hog grind, man, that’s where it’s at, that’s the whole damn thing, right there. You got to be a country boy to know what the bo’-hog grind is, anyhow. I told John Lee Hooker one time, ‘Man, I saw you doin’ the bo’-hog grind on The David Letterman Show,’ and it broke him up. "When I was listenin’ to the jyuck box in Tippo, it was like Tampa Red and Memphis Minnie and the people who preceded Muddy Waters and B.B. King. I learned a lot of those tunes. I used to play ’em at parties, y’know, ‘Let Me Play With Your Poodle,’ ‘My Little Machine,’ ‘Diggin’ My Potatoes’ by Big Bill Broonzy. I dug all that stuff when I was a kid, and Louis Jordan, he was always on the jyuck box. It’s amazing how many people Louis Jordan has influenced. I heard an interview by Sonny Rollins recently and he was talkin’ about Louis Jordan." "The original rock’n’roll?" "I always tell people that the original rock’n’roll band was Tuff Green in Memphis. Tuff Green and his Rocketeers. I used to go to the Mitchell Hotel, man, they used to sneak me in there, ’47, ’48." Memphis in the postwar years had too many great musicians to name here. Andrew "Sunbeam" Mitchell’s hotel was the stopping and jamming place. There are players in Memphis who still remember the impact of visits by the likes of Charles Brown and Oscar Dennard, both classically trained pianists who could play in every key. Allison met men like saxophonist Bill Harvey, B.B. King’s first musical director, and heard the legendary Phineas Newborn Sr. Orchestra at the Plantation Inn in West Memphis. In 1945, Allison had entered the University of Mississippi. "I started out in chemical engineering," he said. "I figured that was a good thing to do to see the world. I think I remember readin’ somethin’ about chemical engineerin’ when I was comin’ up. I did that for the first semester, and then I went to the Army. I was gonna be drafted so I joined the Army for 18 months. This recruiter sold me this bill of goods about if I would join, I’d be able to stay with my buddies. So me and two friends from Ole Miss joined the Army for 18 months, and three days later they went off to North Carolina to the Quartermaster Corps and I went to basic training at Fort McClellan, Alabama. I found out later that was where Lester Young did his basic training. It was about as dismal a place as you can find." The Army, where Allison played with the 179th Army Ground Forces Band, wasn’t a complete waste of time. "When I went to the Army and started playin’," Allison said, "I ran into guys that had been around a lot. I was in the Army with a trombone player, one of the best in the world, Tommy Turk. I had learned to write arrangements at Ole Miss. There was a guy, a musician, one of my early gurus, named Bill Woods, a piano player and a saxophone player, from Charleston, Mississippi. He was one of the first guys who took any interest in me, and he was a good arranger. So when I went over to Ole Miss and started playing with the Mississippians, I started writing arrangements for the band. It was like, three trumpets, five saxophones, the whole nine yards. Arranging was easy for me to do once I got started. In the Army I kept at it, and I met some guys who were arrangers, and they would help me with things. By the time I got out of the Army I’d written a whole book of arrangements for the Mississippians. I think they’ve still got some of the charts down there. When I came back I did a couple of semesters of economics." Allison kept returning to Beale Street, where he saw blues artists that affected him profoundly: "The Beale Street Auditorium, where they had big shows, that’s where I saw the original Sonny Boy Williamson. He was on a show called Smart Affairs of 1949 — it was in ’48 — Larry Steele and his Sepia Revue, with the dancin’ girls and the big band and comedian and the whole thing. I went just for the show, and — I don’t think he was even advertised — he walked on by himself, toward the end of the show, and played a few blues numbers, just playin’ harmonica and singin’ by himself, and it just floored me, man. The power of it — I thought, ‘oh, man, yeah’ — it got me right back into takin’ the blues seriously. Then I left Ole Miss and ended up with an English major, down at LSU. My first gig was in Lake Charles, my first six-night gig. That was the first trio gig that I played." Allison was graduated from LSU with a B.A. in English in spring of 1953. He had been playing clubs in the South for years, and he continued that for a while longer, getting what he calls "on-the-job training." I’d read that he had first worked in New York with Al Cohn, and I asked how they’d met. "I met Al Cohn’s wife in Galveston, Texas — the wife he had at the time," Allison said. "She was a singer named Marilyn Moore. She did sort of a Billie Holiday thing. I was workin’ in Galveston, this was about ’54, I guess, ’55. I met her at a session, she sang and I played behind her. She told me if ever came to New York to look up Al, and she gave me the number and everything. So, eight months later, or whenever I did decide to go to New York, I called Al up, and he had me out to his house, man, to dinner and the whole number, and we played, and so forth, and he started gettin’ me on whatever he could get me on. He wasn’t workin’ that much at the time, he was mostly writin’. But not too long after that, he and Zoot [Sims] started workin’ a lot more, and when they started workin’ at the Half Note, downtown on Spring Street, I used to work with them all the time down there, and I worked gigs just with Al and just with Zoot. "Al was definitely one of my first benefactors up in New York. He put me on whatever he could. He got me on my first record date. The first record I made was the thing with Al and Bobby Brookmeyer and Nick Stabulas and Teddy Kotick. I don’t remember what label it was or nothin’, but it was a good record. Every now and then somebody turns up with it." Allison started recording as a leader with the small jazz label Prestige, went to commercial giant Columbia for three years, then found a home at Atlantic for a decade and a half. His first album under his own name came from a series of short piano themes that he called Cotton Country Suite. The record company thought somehow the word "cotton" wasn’t commercial, and now not even Allison uses the original title: "Back Country Suite — I had been collecting those little pieces over the years. Actually the thing that inspired that was Bela Bartok. At LSU I heard him for the first time, one of his things, the piano suite, ‘Hungarian Sketches,’ or somethin’, just a piano playin’ fairly simple tunes. But they were so evocative. That gave me the idea. I said, ‘Well, hell, I can do that. With my background, the music I grew up with, I ought to be able to come up with somethin’ like that.’ "So I collected those little pieces for the next two or three years, and when I got to New York I had it together and I made a tape of it over at that 34th Street loft — 34th right between Second and Third. Two Mississippi guys were the ones that ran it, friends of mine, so I used to play there all the time. I made a tape of the thing there, and I took the tape around, and I didn’t get any takers for the first few months. Then one night I was at a party where [jazz pianist] George Wallington was playin’ — he had an apartment up there on the West Side — and I played some of the pieces from Back Country Suite for him. He said, ‘Look, man, I can probably get you a record date at Prestige,’ ’cause he knew Bob Weinstock. So he took me ’round to Prestige, and they signed me right there to do six albums in two years — 250 dollars an album. So that’s how that came about. "I gave George the publishing end of it — he had a publishing

company, Jazz Editions — which I’ve regretted ever since. I finally got

it straightened away after a long time and after a lot of money. But

"Speaking of that, what did you think when the Who cut ‘Young Man Blues’?" "I got a check in the mail from Jazz Editions for $7000. I thought, ‘Man, what the hell is this? This must be some mistake.’ I’d been gettin’ 20 dollars and 30 dollars, and I couldn’t figure out what had happened. I didn’t know anything about ’em [the Who]. I had heard about the Rollin’ Stones. I ran into the Rollin’ Stones. I played on a show with them in about ’66. [Actually August 7, 1964.] At a place called Richmond, outside of London, on a soccer field. It was a blues festival, and all these English blues people were there. That’s when Brian Jones, the blond guy, was still alive, and he was the star then. Mick Jagger wasn’t the star. I had never heard of ’em — they had to be brought in in a covered van. I didn’t realize that kind of thing was going on. It was amazing the adulation those guys were gettin’. And when they did their show, I couldn’t believe it, Brian Jones would go out and shake his locks, man, and all these teen-age girls would go crazy. Ten, 15 thousand people there — it was frantic. It was new for me to see that that was happenin’, and people were sayin’ what did I think about it. I said, ‘Well, it’s better than Lawrence Welk and Guy Lombardo, helluva lot better than the Hit Parade.’ But it was a few years later, I guess, that the Who did the thing, the first time I ever made any money off a record. "I’ve made a few bucks from some of my songs that the rockers have done, but as far as my records go, they’ve never paid out. None of my records have ever gotten out of debt. I owe all the record companies money. I was with Atlantic for 17 or 18 years [actually from 1961 to 1976, but it seemed longer] and made a lot of records for ’em, and I got my first royalty check from Atlantic last year. Because of a reissue they did, they had to pay me a coupla hundred dollars royalties or sump’m. But all the time I was with ’em I never made any money except what I got in advance." "In 1996 you did that thing (Tell Me Something, Songs of Mose Allison on Verve) with Van Morrison and Georgie Fame." "Yeah, right, and I’m still tryin’ to get the money. I’ve gotten paid for just a fraction of what it’s sold, man. I don’t know what I’m gonna do, but I gotta do sump’m, it’s been about 18 months now since it came out. By all reports it’s sold over 200,000 copies, I’ve gotten paid for 30,000." "You must have enjoyed your years with Atlantic, though." "Oh, yeah. I loved [Atlantic Records producer] Nesuhi Ertegun, man. You mentioned Jerry Wexler, he was the one tryin’ to get me to go do somethin’ commercial all the time, I used to hate him. He was always tryin’ to get me to go down to that place down there where they had that rock’n’roll band, Muscle Shoals, tellin’ me how I could start sellin’ records and all that. So whenever he comes on the programs as some kind of scholar or sump’m, I always snigger a little. "I used to hang with Nesuhi a lot, he was my man for a long time. In fact, he’s the one who kept ’em recordin’ me even though I wasn’t sellin’ any records. I was sorta like the mascot there for several years. They kept comin’ up with these suggestions, and I kept ignorin’ ’em. But I was able to do pretty much what I wanted to do." Until he wasn’t. In the 1980s nobody was rich enough to afford a mascot. Allison for several years was without a label, until he signed with Elektra/Musician in 1981, where he made two albums, Middle Class White Boy and Lessons in Living. That association led to his affiliation with Blue Note, a venerable jazz label with four Allison titles currently in release. The latest one, Gimcracks and Gewgaws, was released in January, which more or less brings us up to the present. With chronology for the moment satiated, we return to philosophy, aesthetics, metaphysics. "I did an interview with Ray Charles recently," I said. "And it kind of gratified me to hear him bring this up, ’cause it’s something I’ve thought many times. You get to where you think, ‘Maybe it’s just me, maybe I’m the only person who feels like this.’ He started talkin’ about people we listened to comin’ up, whoever it was, Johnny Mercer or Jo Stafford or Frank Sinatra or Billie Holiday. Ray made the point that with these people, you heard one note and you knew who it was. Instrumentalists too. Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Pee Wee Russell — one note and you know it’s Pee Wee Russell. Ray was saying, ‘I don’t know — if you know some people around today like that, tell me, ‘cause I’d like to check ’em out, but I don’t hear it.’" "Everybody’s singin’ that same song," Allison said, "and they should be singin’ it, because it’s true. I just saw Nat Hentoff bein’ interviewed. He was sayin’ the same thing. He said, ‘Man, these young guys, they can play anything, they’ve got all the technique in the world, but none of them have any personality, and it’s really a shame, it’s a loss, because there’s no real personal expression.’ A lot of players, a lot of young journalists, man, they never heard of anybody. Haven’t even heard of Charlie Parker, a lot of ’em, you know." "Record companies are trying to sell what they put out this week, and to hell with the rest of it." "That’s the only saving grace about Europe. They take a look at the whole thing — they still dig guys, 80-year-old players over there, and they know a lot about the early music." "In Europe they know better what art is. In America jazz is not art." "It’s the commercial thing," Allison said. "And New York is like one-upmanship. I saw Lester Young on his last gig in New York at the Five Spot on the Bowery. It was on a weeknight, and there were like 10 people there, the waiters were makin’ noise with the chairs, and all this stuff, and he wasn’t gettin’ any respect, and he was playin’ beautiful. He sounded beautiful. Next week Ornette Coleman was there, they were lined up around the block — you couldn’t get near the place. That pretty well sums it up."

get the hard-copy version of BLUES ACCESS.

|

that happens to everybody; it takes a while to find out. George is dead

now. His brother took over Jazz Editions, and that’s who I had to sue to

get my rights back. But foreign copyright laws are different, so Jazz

Editions still has the right to collect half my money in foreign

countries on tunes like ‘Parchman Farm’ and ‘Young Man Blues.’

"

that happens to everybody; it takes a while to find out. George is dead

now. His brother took over Jazz Editions, and that’s who I had to sue to

get my rights back. But foreign copyright laws are different, so Jazz

Editions still has the right to collect half my money in foreign

countries on tunes like ‘Parchman Farm’ and ‘Young Man Blues.’

"